The call of firefighting and emergency response is dangerous business. Beyond the occupational risks of physical injury or death in the line of duty, firefighters also face serious health threats from elevated and frequent exposure to carcinogens and toxic chemicals brought back to the firehouse from the fireground.

Recent trends built around Hot Zone Design strategies are now re-shaping the way architects and fire departments approach contaminant control within the station. Just as important, however, is the need for similar revolutionary thinking to address another quiet crisis—the equally insidious mental and emotional health threats that challenge the well-being of our emergency responders.

The Ruderman White Paper on Mental Health and Suicide of First Responders (2018) summarized the issue: “First responders witness horror on a daily basis. These men and women, including firefighters, law enforcement personnel, and EMS workers, have front row seats to the horrendous aftermath of natural disasters, terrorist attacks, violent domestic disputes, traffic accidents, and more. Many first responders have military experience, and therefore their experiences as first responders pile onto a career that is already rife with trauma. Constant exposure to death and destruction exerts a psychological toll on first responders, resulting in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, depression, and even suicide.”

A source of hope

Emergency responders are not alone as professionals in facing traumatic workplace experiences. Medical and healthcare providers also experience daily trauma in dealing with injuries, illnesses and death in the care of their charges. Moreover, patients, victims, families and loved ones also struggle with emotional and mental trauma when medical and health challenges arise. Fortunately, new trends in healthcare architecture bring fresh insights on healing and human biology to offer a source of hope for firefighters, police officers and other emergency responders.

In recent years, the field of healthcare architecture has innovated, developed and implemented several design strategies that deftly link basic human physiology with built environments that encourage physical, emotional and mental healing. Those strategies include increased attention to circadian rhythms, daylight, color, views of natural settings, and selection of materials. This concept, known as Immersive Design, adapts these strategies for fire and rescue facilities, offering tantalizing promises to improve the wellbeing of our emergency responders.

Circadian rhythms

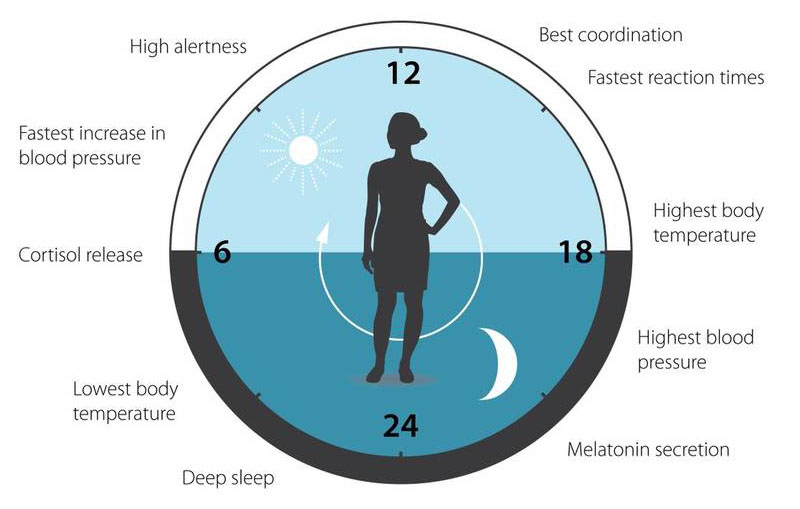

Immersive Design uses lighting, color and nature to improve the emotional health and wellbeing of the public safety community. Natural lighting has a profound effect on our bodies. It is used to regulate our circadian rhythm, which controls the daily physical, mental and behavioral changes happening to our bodies. Responding primarily to light and darkness, natural circadian rhythms control such functions as behavior, hormone levels, sleep, eating habits and digestion, body temperature, and metabolism.

“A carefully calculated circadian rhythm adapts our physiology to the different phases of the day,” explained Juleen Zarieth, professor of Integrative Physiology at Karolinska Institute.

The natural rhythm of the sun provides for different shades or colors of light throughout the day, which the body’s endocrine system uses to set our human biological clock. Beginning with a peak concentration of blue light in the morning, which helps reduce sleepiness and “wake us up,” mid-day color changes increase our alertness and reaction times. As the day progresses to evening, the natural lighting turns to shades of amber, which clues us to seek a restful night of sleep. Recent work by the 2017 Nobel Laureates Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young confirmed this theory.

Lynn Peeples noted in her article “Age of Enlightenment: The Promise of Circadian Lighting” (undark.org/article/circadian-lighting-human-centric-lighting): “Too little light from the blue end of the visible spectrum during the day, or too much of that same light at night, can cause an internal clock to slip off beat, setting off a cascade of potential consequences. These include not just poor sleep, reduced concentration, and contrarian moods, but over the long-term, increased risk of depression, diabetes and cancer.”

To read more of this article visit Firehouse Magazine: Embrace Immersive Design

If you are interested in learning more about Immersive Design and how it can be applied in your station, register for the 2019 Firehouse Station Design Conference or contact Paul Erickson at 703-956-5600 / perickson@lewarchitects.com.

Note: Circadian rhythm image by Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, Illustrator Mattias Karlen